Pictures of Amsterdam University College’s creative writing students

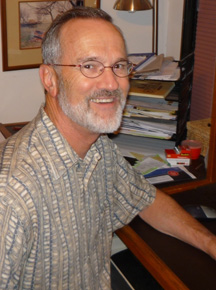

Amsterdam University College’s two creative writing classes are hoping for hands-on experience with literary magazines by reading through Superstition Review’s poetry submissions. They’ve interviewed SR’s poetry editors—Madison Latham and Au’jae Mitchell—to better understand what SR looks for in a poem, how they balance reading submissions between them, and to get to know them. Some responses have been edited for clarity.

Amsterdam University College: What are your criteria for choosing poems?

Au’jae Mitchell: My main criteria for choosing poems is rooted in three questions: Does it incite feelings inside me? Does it feel like the poem has something important to say? And is it unique? A poem or collection of poems that has a positive answer to all three of these questions is one that I contend for and am passionate about. Poetry is an artistic form of expression that ranges in structure and execution, but every poem, despite this diversity, can accomplish absolutely powerful things.

AUC: Do you discuss with one another what you choose or do you split work between the two of you? How long does it take for the two of you to agree? What’s the collaboration aspect between you?

Madison Latham: We use a platform called Submittable. Our founding editor, Patricia Murphy, assigns us poems to read through and vote on. We vote on the same poems and meet with each other—as well as Patricia at the end of September—and discuss the poems we voted yes on.

AUC: Do you consider the poets’ experience or amount they’ve published?

ML: We publish both emerging and established authors. This could range between one and a hundred previously published poems, to someone who is a part of an MFA program.

AUC: Is there a limited number of pieces you can publish in a given issue?

ML: There is no cap for how many authors we will take. In previous issues, it has ranged from 10-15, but we decide based on the poet and the collection of poems they have submitted. We may publish one of their poems, or all of their poems. It can vary, but there is no set number during a reading period.

AUC: To what extent do you edit the poems before publishing them?

ML: We do not. There are no revisions accepted for poetry submissions. If a poem needs revising, we vote against it. We get so many submissions that we always have enough polished poems to publish.

AUC: Is there any content that you refuse to publish?

AM: We do not publish harmful, disparaging, or discriminatory content.

AUC: How do you decide on the order in which the poems are published?

ML: Poetry is published in the issue alphabetically by the author’s first name. Each author receives a page that includes their bio, headshot, selected poems, and an audio recording of those poems. Issue 29 demonstrates how the poetry section is organized.

AUC: How many submissions do you get in a submission window?

AM: This semester we received more than 422 submissions in poetry. These were narrowed down to 55 submissions to consider for Issue 30 of Superstition Review.

AUC: Do you write poetry?

ML: I do! I finished my capstone in poetry at ASU last semester (Spring 2022). I still write poetry in my free time, but I also enjoy reading work by other poets—which is why I wanted this position.

AM: I do write poetry! I write poetry in my free time between research for my Master’s program and my narrative writing. It is very hard for me to sit down and write poetry, so most of the poetry I write I jot down in my notes at spontaneous times during any given day and build upon that initial thought.

AUC: Is there anything you’d like to add?

ML: Thank you for your interest in SR and our work! We accept submissions from any creative writer that is not an ASU undergraduate. Our submission period for Issue 30 has closed, but we will begin accepting submissions for Issue 31 in January 2023.

AM: To any aspiring poets, writers, or artists, I encourage you to consider submitting to Superstition Review. And to all creative minds out there considering putting themselves and their work “out there” for consideration, I believe in you and what you can do!

AUC’s creative writing classes consist of 25 students, each with different majors and many from international backgrounds. Later, they will be selecting poetry from Superstition Review‘s submissions, which will appear on our blog!