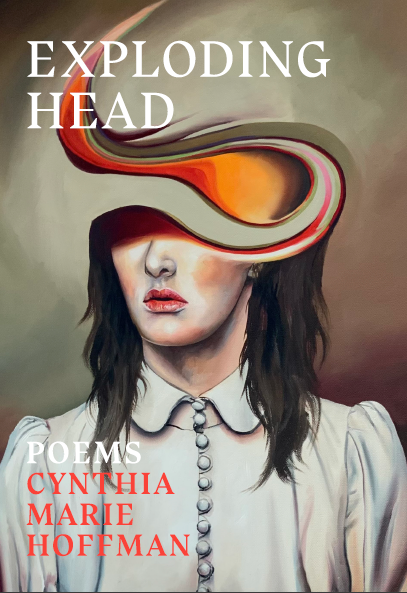

Congratulations to past contributor Cynthia Marie Hoffman who has a new poetry collection coming out on February 6th entitled Exploding Head.

This collection of prose poems chronicles a woman’s childhood onset and adult journey through obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), which manifests in fearful obsessions and counting compulsions that impact her relationship to motherhood, religion, and the larger world. Cynthia Marie Hoffman’s unsettling, image-rich poems chart the interior landscape of the obsessive mind. Along with an angel who haunts the poems’ speaker throughout her life, she navigates her fear of guns and accidents, fears for the safety of her child, and reckons with her own mortality, ultimately finding a path toward peace.

This book has received significant praise:

“Hoffman’s fourth book compresses the relentlessness of fear and obsession into electrifying prose poems, boxes threatening to burst. Hoffman scrutinizes the child self and the mother self with absorbing candor, precision, music, and urgency in this harrowing world where ‘birds bomb through the air like the skulls of galloping horses.’ The impulses that sprint through the mind—‘a shuddering animal hunkered down inside your skull’—come so frightfully alive that I felt I’d been transported into another woman’s extraordinary brain.”—Eugenia Leigh, author of Bianca

View more of Cynthia’s work on her website. Purchase Exploding Head here.

Cynthia Marie Hoffman is the author of four poetry collections: Exploding Head (Feb, 2024), Sightseer, Paper Doll Fetus, and Call Me When You Want to Talk about the Tombstones, as well as the chapbook Her Human Costume. Hoffman is the recipient of a Diane Middlebrook Fellowship in Poetry at the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing, an Individual Artist Fellowship from the Wisconsin Arts Board, and a Director’s Guest fellowship at the Civitella Ranieri Center in Italy. Her work has appeared in Smartish Pace, Fence, diode, The Journal, The Missouri Review, and elsewhere. Collections have appeared as an intro feature in Pleiades, a featured chapbook in Mid-American Review, and in the annual Introductions Reading Loop online at Blackbird.

View Cynthia Marie Hoffmans’ poems “This Is All True,” “Protection Spell Jar,” and “If You Have Grown Unrecognizable to Yourself” in issue 30 of Superstition Review.