When my husband and I recently took a road trip with our two young children, the talking was deafening. As we hit open highway surrounded by mostly trees and hills, my husband tried to play a game. “OK, I’m going to count to 15 and see who can stay quiet,” he said. The record for silence in the car that day was about six seconds.

Silence is an interesting concept. Pre-children, when I was surrounded by too much of it, I created noise and clamor: turned on a fan, tapped my pencil against my desk, hummed Blondie. I rebelled against either its calmness or vastness that forced me to think too much. These days, as a parent of young children who barely let me finish a full sentence or a thought or a line of poetry, silence is a locked room whose key I lost in some dream years ago.

Silence is an interesting concept. Pre-children, when I was surrounded by too much of it, I created noise and clamor: turned on a fan, tapped my pencil against my desk, hummed Blondie. I rebelled against either its calmness or vastness that forced me to think too much. These days, as a parent of young children who barely let me finish a full sentence or a thought or a line of poetry, silence is a locked room whose key I lost in some dream years ago.

I was reading an interview with Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and memoirist Tracy K. Smith on femmeliterate, where she talks about 21st century feminism, being a teacher of language, social responsibility as a poet and how motherhood has changed her writing. She had an insightful take on it, which was that caring for young children has forced her to develop a lightning-reflex creativity and agility – and this new form of response crossed over into her writing process:

I have to pick someone up from school, drop somebody off, etc., etc., so my ritual or my practice is when I have the time, and I know I need to get down to work, I just get down to work. And oddly enough, I think those constraints made me more productive. When I was younger and living alone, I could waste all this time, and I could kind of just tinker with things slowly; now there’s a real hunger when I have the space …

I’ve been thinking about the ways my life changed – mostly since having my second child two years ago. The demands of caring for small children has its many ups (all the firsts, the enchanting laughter, the hugs, etc.), downs (tantrums, projectile vomiting, the aforementioned unceasing talking and activity) and the unexpected (how the energy and needs of two children seems to create its own tornado that only quiets when they’ve gone to sleep). At the end of the day, it’s hard, no, let’s say almost impossible, to push my tired, still-feeling-like-post-pregnancy body and mind into writing and editing mode.

I was reading Amy Clampitt’s poem, “A Silence,” and kept re-reading this part, which shows all the chaos we’re surrounded by (all kinds of disordered things) and how after processing them, a (creative) silence opens:

beyond the woven

unicorn the maiden

(man-carved worm-eaten)

God at her hip

incipient

the untransfigured

cottontail

bluebell and primrose

growing wild a strawberry

chagrin night terrors

past the earthlit

unearthly masquerade

(we shall be changed)

a silence opens

For writing parents, that silence might be different than what it used to be. As I steal time here and there even to write this blog, the dishwasher runs noisily behind me, my daughter is playing a loud game on her tablet and my old cat is meowing for his night food. It’s hard to sink deep into that creative trance I used to get into before when I really did have hours of silence. So it’s two things: It’s writing through the din, and it’s also looking for a space and time to secure that needed and actual silence.

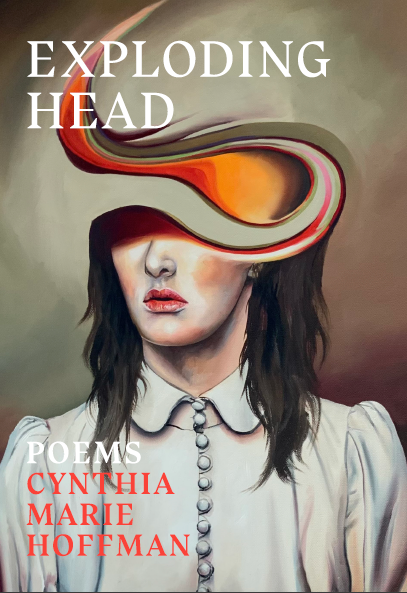

What’s seemingly contradictory to me saying how exhausted I am and how hard it is to write is that this year and early next, I’ve got three chapbooks and my first full-length poetry collection coming out. Ray Bradbury wrote, “We are cups, constantly and quietly being filled. The trick is, knowing how to tip ourselves over and let the beautiful stuff out.” This feels true, in that having children opened me up (bodily and spiritually) in a way I hadn’t been before – and both vulnerable and resilient in a way I hadn’t been. I found strength in the ability to grow my children, but also to persevere in my work. But like Bradbury wrote, you need to know how to tap your tired self to let our writing fodder out.

Being a mother writer, I often feel that I shouldn’t ask for help, or that I should be able to nurture my children all the time, and work at the job that pays me a salary, and then also do the writing that fuels my heart. And do it all in the clamor, in the middle of the fatigue. A few weeks ago on a Saturday, I went to the dentist to get two cavities filled (my children were at my parents’ house). When I got home, my lips hung strangely because of the Novocain and I couldn’t speak clearly: Yet the house was strangely silent. It was like floating underwater. I felt hungry. For one hour, I wrote, rewrote and edited in the bright sunlight and was nourished in a way I hadn’t been.

In that same interview with femmeliterate, Smith also talks about being strong enough to know she deserves to take time away from mothering for her creative work. That’s an area where I still struggle, in acknowledging that it’s OK to take time away from parenting, that perhaps it doesn’t have to be at 5 am or midnight, when I should be sleeping. That I can find an easier way to make it work, instead of making it hurt when I take that time:

… it’s really important to find a way to secure that time and space to make the work. As a mother there are so many demands that it’s a genuine struggle to say ok, I’m not going to be a mom for two hours; I’m going to write. But I think it’s essential to do that: enlist somebody to help you with your child so you can be a writer for part of your day. … it’s really important to create security for the writerly self that is a woman and that is an author. Without apology.

Listen to Franz Kafka who wrote, “You do not need to leave your room. Remain sitting at your table and listen. Do not even listen, simply wait, be quiet, still and solitary. The world will freely offer itself to you to be unmasked, it has no choice, it will roll in ecstasy at your feet.” And it seems so simple – find the silent time and the whole world will come to you, so you can translate it into your art. But parenting and writing are never simple, of course, so as I write now into dusk, into squinting through my glasses at this bright screen, with my son calling good night, mama over and over, I commit to writing through the din and then making my own silences (where I can transfigure what world I find).

Nicole’s website