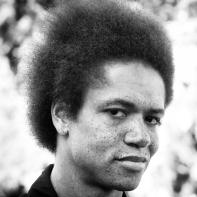

Elwin Cotman

Elwin Cotman is the author of three collections of speculative short stories, The Jack Daniels Sessions EP, Hard Times Blues, and Dance on Saturday. His next book, Weird Black Girls, is forthcoming from Scribner in 2024. His debut novel The Age of Ignorance will be published by Scribner in 2025. Cotman’s work has appeared in Grist, Electric Lit, Buzzfeed, The Southwestern Review, and The Offing, among others. He holds a BA from the University of Pittsburgh and an MFA from Mills College. He writes this and that on his Substack.

“Surrealism Functions as Color” an interview with Elwin Cotman

This interview was conducted via e-mail by Interview Editor Madelynn Paz. Of the process she said, “Weird Black Girls is a triumph; Cotman’s visceral, lyric prose and complex narratives blend surrealism and myth into worlds only he could create. Within each story, Cotman’s characters reveal the simultaneous beauty and monstrosity of human nature. It was a privilege and a pleasure to explore his thoughts on craft, his writing process, and some of his authorial influences.” In this interview Elwin Cotman talks about experimenting with narrative structure, how poetry influences his prose, and staring into the abyss of racism.

Superstition Review: You do so many interesting things with narrative in this collection. I was particularly intrigued by the circular structure of “Things I Never Learned in Caitlin Clarke’s Intro to Acting Class,” which is further complicated by the protagonist's time traveling through their lover’s memories. How does structure enter your narratives? Is it something you have in mind before writing or something that emerges more organically?

Elwin Cotman: I think about structure a lot these days. The sense of escalation that comes with “rising tension” simply doesn’t feel right for every story. So I’m exploring alternate structures in the stories I‘m writing now. In Weird Black Girls the changes in structure either happened organically or as a response to feedback. For instance, the circular narrative in “Caitlin Clarke” grew from my choice to get more surreal with the protagonist’s powers. I added new elements to those powers on the suggestion of my friend Alex Smith, another writer. From there the narrative evolved. Another example is “Reunion.” It’s a dialogue-based story where one of the protagonists lists different topics at the start. After he and the other protagonist exhaust these topics, the story ends. It’s basically narrative-as-grocery-list. I didn’t realize I’d written an alternate structure until I was thinking about it last week. Now I want to write other stories in that vein. The only piece I went into with a specific idea about structure was the title story. It takes place over a weekend, a picaresque where a former couple work through their issues by literally moving through the world together. Nothing propels them towards an understanding—they have to spend time in each other’s company. Movement is the engine that drives the story. I kept tight to that structure all through writing and revisions.

SR: The language in Weird Black Girls is breathtakingly lyrical; the descriptions of urban spaces, especially the fantastical Boston of the title story, are filled with unusual and arresting comparisons. How has urban exploration, as well as your work in poetry and performance art, influenced your prose writing?

EC: I regularly read poetry to get myself thinking about language. It’s easy to fall into patterns so poetry helps shake me out of them. Similarly, my favorite prose writers are the ones who use language in exciting, ecstatic ways. At the time I started writing “Weird Black Girls,” I was reading The Scarlet Letter. It’s a breathtakingly lyrical novel. A lot of Hawthorne’s tics worked their way into the DNA of the piece, and over time other influences magnetized to the story, giving the language vibrancy and diversity. The way I looked at it, in a story so fantastical, the language should be equally fantastic to the world that I’m creating. It’s funny that my interests in poetry, flaneurism, and performance osmosed at the same time. After college, when I was teaching in DC, I would sometimes take walks around the University of Maryland—College Park. One night I’m walking by the Writers’ House and I hear music coming out the open door. I followed it like a siren song. Where I ended up was the TerPoets open mic, which was organized by the poet Henry Mills. Becoming a regular reader at TerPoets was huge for my development as a writer. From there, I became interested in modern poets, many of whom are writers I look to for inspiration. We’re living through a Golden Age of poetry right now. At TerPoets, I learned to appreciate the stage as its own unique communication between me and my audience. And I still love the mystery of exploring cities, though nowadays there’s less walking on my end, more Ubering involved.

SR: The voices of each protagonist are incredibly distinctive; each character has great complexity and emotional depth. I particularly admired the voices of your female and femme characters, such as Shirley from “Switchin’ Tree” Spike from “Triggered” and the narrator in “Things I Never Learned in Caitlin Clarke’s Intro to Acting Class”. Where do your characters come from? How do you access them and embody their voices on the page?

EC: First of all, every protagonist starts off as me. I write what I know and can’t pretend otherwise. There’s something in their experience that mirrors my own, but at some point in time they made a choice I wouldn’t have, and in establishing that choice, I can work backwards to flesh out their past. Eventually I have a new, imaginary person to play with. My characters’ unique experiences influence their voice. Like in “Owen.” I have no clue what it’s like to be a war veteran, but that very gap in my knowledge made me want to write from that perspective. And I look at things sociologically, as well: under capitalism, humans are taught to basically be robots. At birth you’re assigned a role and woe be unto you if you don’t follow it. Characters are only interesting insofar as they break away from that role, either by choice or outside influence. The father in “Owen” has a certain sensitivity because he’s been in battle, which reflects in his voice. Then you have Shirley and the protagonist in “Caitlin Clarke” who break from gender roles, and Spike, who can only challenge her role as a white woman to an extent. In the ways they rebel, I find the characters. Then I find their voice.

SR: There are many moments in the collection where the surreal nature of the work envelops the reader, and the act of reading the story itself becomes an uncanny experience. “Reunion” for example had a wonderfully disorienting effect, juxtaposing literal surreal events with the complexities of a white woman and an African American man discussing the Black experience and police brutality. How do you balance the speculative elements within your stories while maintaining the coherency of the narrative?

EC: “Reunion” was based off of a conversation I had with my friend Dan McCloskey. He said, if fantastic things happened, we would simply find a way to explain them as normal. That’s what the characters are doing—denying the sublime from the outside world, as well as the sublime they see in each other. For that particular story I made sure to constantly check in with the characters and see how they were reacting to one another internally. In a good fantasy story, the human relationship is at the core. Surrealism functions as color—without those impossible elements, “Reunion” wouldn’t even be a short story. It would be a film or stage play. There was a point in the writing process when I went back and added more surrealism just to create a better balance between the fantasy and the character work. I don’t think there’s a single speculative piece in the book that couldn’t have been, with some tweaking, a regular story. But where’s the fun in that? I have no more desire to write about two friends just talking than C.S. Lewis wanted to rewrite the Gospels or Tolkien wanted to describe being in the trenches. Adding surrealism gives me that dopamine rush that draws me into the writing. And you can’t force it. If I ever have a story where I’m struggling to include a supernatural element, I know immediately that it’s a straight literary piece.

SR: You mention Zora Neal Hurston, Liz Hand, and Mary Gaitskill as influences on your work. You also thank Gaitskill in your acknowledgements and list her as “the world’s greatest living writer.” How have these authors shaped your writing, and how do you see Weird Black Girls in conversation with their work?

EC: I’ll go in order: I read Their Eyes Were Watching God pretty late in life, in my 30s. It’s a relentlessly good book in every way but particularly the pacing. Zora knows when to speed up and slow down. Every sentence is perfect in that it conveys exactly what is needed to be conveyed, not a single word wasted, yet at the same time, every sentence carries some element of lyrical magic. Reading Zora let me know that I was on the right track as far as writing about black folk life, which she did, often through fantastical scenarios. Liz Hand changed my view of what a fantasy story could look like when I read her collection Saffron and Brimstone. Her stories were dark and baroque, but also subtle; there’s one story, “The Least Trumps,” where it’s like I can’t even see the fantasy on the page. I feel it somehow. That’s the level of craft she's working at. She’s writing masterpieces constantly. Reading her work is what it must have been like to watch Shakespeare in real time. No one is better at exploring the human heart than Mary Gaitskill. She knows the right metaphors, similes, adjectives, whatever to show the contradictory feelings people go through. Because she can do this, she’s able to come at even the darkest subject matter from a place of empathy. There are many stories of hers that shouldn’t work. Where I think, “How can these fucked up people have a happy ending?” Or, “How can I possibly care about this person?” But because she’s so good at getting in their heads, everything makes sense in the end, whether or not you want it to make sense. Whether or not you agree with her sensibilities. Whenever I need to remind myself what prose is capable of, I read her. It’s like taking a defibrillator to my brain.

SR: Your previous essay in Electric Lit “Why Are We Learning About White America’s Historical Atrocities from TV?” discusses the blind spots and intentional erasure of violence against African American communities within the American education system. When American history is whitewashed in this way, it falls to us to educate ourselves. How might your book (and others that have influenced you) help address some of these gaping holes in our education system?

EC: That was such a pandemic essay. “All I do is watch streaming shows so that’s what I’m writing about.” Electric Lit is lucky I didn’t send them a paper analyzing sex scenes in Outlander. I don’t know if my work can help educate people. The forced ignorance in American society has reached critical mass. There’re people out there who should be reading my book but won’t because they avoid black authors and, with black writing being banned in schools, probably won’t ever be exposed to our work. But I don’t write stories to educate. I write to make sense of my world. Even “Triggered,” which I wrote with a white readership in mind, is a commentary on things I have seen, not an attempt to change their minds on anything. To learn empathy, people have to be open to it in the first place. I wouldn’t be shocked if my books were outlawed next year. White supremacists aren’t avoiding our books—they’re banning and destroying our books. They do so because they know what those books say. You don’t ban a novel like Beloved unless you know the power within it. How opening to the first page of that novel completely destabilizes this world white supremacists have created; completely upends the myths they teach as facts. As far as I’m concerned, anyone who seeks out a book like mine has already done most of the work towards educating themselves. That is, they are a person who wants to be educated. That’s the important thing.

SR: The setting of “Triggered” takes place in an anarchist, punk DIY community of activists, and the hypocrisy and victimhood of both the white women characters, Spike and Tiffany, is visceral, even nauseating, in its realness. How do you push past, (or use) what is painful about racism and bias, both the implicit and explicit, in order to make art?

EC: I use that disgust. “Triggered” is very much a stare-into-the-abyss story. Without pulling back the curtain too much, I based it on the story of a black activist who was murdered in Oakland. I had a conversation with a white activist who attended the funeral. They made fun of the funeral. Just laughed it up about the mourning rituals the black folks were doing. It was a horrifying moment. And I said to myself, “This is the kind of person who latches onto black and brown struggles. And this is what they truly think of the people in that struggle.” The character Tif, racist as she is, never has a “mask off” moment as egregious as the one I witnessed in real life. When it came to “Triggered,” I needed to get these thoughts out of my head and onto the page, else I would go crazy. Spike and Tif are written to be disgusting characters, their relationship a microcosm of unsavory dynamics going on in the Bay, post-Occupy. It was also a response to stories I would see in the media. Shows like The White Lotus or Search Party where the creators bend over backwards to portray their characters as entitled monsters swallowing up resources from underprivileged communities, yet still want to make them “relatable,” and, while racism is a key part of the characters, it’s brushed off as the least interesting aspect of their narcissism. I grew up with fucking Friends, which was even worse; characters whose elitism was so great it actually warped the psychogeography of New York City; non-white people couldn’t even get physically close to their incestuous little club. The racial aspect is something you can’t brush off. These characters exist because of racism. White identity politics is the bedrock to everything they are. “Triggered” is a story about loathsome people. Sure, they have characteristics that make them realistic, but I never wanted the readers to root for them or even be impressed by them. Part of why I love tragedy is that it allows me to enter that allegorical space. In Melville’sBilly Budd, Billy is pure good, Claggart is pure evil. In Moby Dick, Ahab is pure megalomania. Writing a tragic story from the villains’ perspective allowed me to write Spike and Tif as archetypes. Looking away from the disgusting things they represent would do a disservice to the story and the world it reflects.

SR: Both “Owen” and “Switchin’ Tree” have complicated depictions of the relationships between parents and children: how they can be a nuanced blend of violence and tenderness, and involve fear stemming from the need to protect young black children from a society that is dangerous for them. I also noticed you dedicate this collection to your father, Dr. Elwin Cotman. Can you speak to how your relationship with your father affected your development as a writer, and these two stories specifically?

EC: The first thing I ever feared was the dark. I would sit up in bed, staring into the corner, imagining what demons lurked there. The second thing I feared was getting my ass whipped by my dad. One fear is primordial, the other very human. Spanking is a form of theater that adults subject children to, a pageant that is purposefully drawn out, focused as much on making the child feel ashamed as it is on making them fearful, and other than Santa Claus, it’s the only kind of play that parents in our society are encouraged to take part in. I’ve always thought the concept of spanking was rife for exploration in a horror story. I don’t know if black parents still hit their kids, but in my generation they did. And it’s fascinating to me because the parallels to slavery are obvious. In a lot of ways, it’s like our attachment to Christianity—everyone knows the religion was forced on our ancestors, but over time we decided, not only were the slave masters right about which deity to worship, they were right about how to discipline wayward black people. If it wasn’t for my father, I wouldn’t be a writer. He introduced me to stories. He is a gentle person. More than that, he’s a non-confrontational person. If you’ve ever watched House of the Dragon, my dad was basically Viserys. But he was capable of shocking brutality when it came to me. It was like a switch turned on in his head; the need to believe, if he set me on the right path, that would somehow keep me safe. Obviously, there’s nothing you can do to keep black children safe. My dad never enjoyed hitting me, and the futility of spanking, the tragedy in this choice he felt he had to make, carries so much cultural weight. Hence, I wrote about it.

SR: Anime, comic and video game culture are an important element of “Tournament Arc.” There was a particular line in this story spoken by the protagonist regarding representation that resonated deeply with me: “ …as a child I never saw myself in the stories I loved. The epics. Those tales that felt like they mattered. Boys like me, girls like her played the token, the help, the wisecracker who died first. Certainly not the hero… anime was not white, precisely what I needed at the moment… to find my best self.” How has becoming a writer helped you find your best self? How do you see yourself in the characters you create now?

EC: As in they’re all middle-aged grumps? The character is talking about inspiration he found through the TV shows and movies he watched. I think I had that feeling, too, when I was younger. This is particularly true for something like anime, where so many protagonists are pure-hearted in ways I rarely saw in western media, and their stories were told with utmost sincerity. Nowadays I relate to media differently. If I watch Cowboy Bebop, I’m not so much inspired by these flawed, melancholy, cynical characters—beautiful as they are—so much as I’m nodding along thinking, “Man, these creators were right. Life is like that sometimes.” I don’t know if I’ve found my best self through writing. Without a doubt, I’ve grown as an artist. But a lot of what I’d consider personal improvements have simply come with getting older. I look at this entire journey as an education. I’ll graduate when I die. Whatever I was, in the end, was my best self.