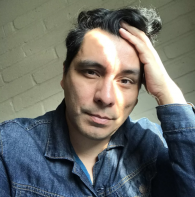

Manuel Muñoz

Manuel Muñoz is the author of two previous collections and a novel. He is the recipient of a Whiting Award, three O. Henry Awards, and has appeared in Best American Short Stories. A native of Dinuba, California, he lives in Tucson, Arizona.

“This is Really a Novel,” an Interview with Manuel Muñoz

This interview was conducted via e-mail by Interview Editor Rich Duhamell. Of the process, they said, “Like bringing the periphery to centerstage in his work, Manuel Muñoz’s openness about the struggles of bringing The Consequences to publication helps dispel the myth that it gets easier, when in fact, the author just gets better to meet every new challenge. He has stayed true to his creative visions throughout the years, and this commitment has brought us some of my absolute favorite short stories of all time.” In this interview, Manuel Muñoz talks about reoccurring characters, beloved mentors, and the resilience in deciding the self is the only audience that needs to be pleased.

Superstition Review: The concept of consequences throughout the collection sits heavy in these character’s bones like resignation, surrendered to routine yet still finding moments to break free from the monotony — for better or for worse. What was it like crafting these characters spanning the whole range feeling toward obligation, from never considering an alternative to “I don’t believe I have to answer to anybody. Not even God. When I get old…I’ll go right up to the edge of the Gulf and walk straight in”? Which was the hardest to flesh out?

Manuel Muñoz: The characters who don’t consider alternatives are the ones who are the most difficult because they might not know how to go about listing options even to themselves. Goyo, on the other hand, was much easier: he’s the character who speaks that last line and he’s declarative and forceful about it. But he’s not the protagonist of the story. What intrigues me is less what he says and how Bea—who is the center—reacts to it and thinks about whether she could say something similar. It’s often the secondary characters who prompt some change in my protagonists.

SR: “If you don’t tell your story, someone else will,” you said in an interview with World Literature Today of writing stories about interrupting presumptions, and you’ve called “Fieldwork” “as close to autofiction as I get.” In the sacredness of receiving and immortalizing these stories of Chicano and migrant worker communities that are still so little heard from directly, how do you balance being a faithful reteller and telling your own story with it? How do you gauge how much of a filter of fiction to layer without becoming just another misconceiving eye like the many ready for gossip in this collection?

MM: I’m working on the presumption that most people approach my stories as if they are true. Right now, I think most people think about my biography—where I am from and how I grew up and so forth—and it’s inescapable. In fiction, though, I’m the only person who knows just how fine that balance actually is. Even in sharing that some details are quite close to truth, I rarely specify which are not. That’s the shield that I appreciate in fiction and allows me to work. I would only worry about being a truly faithful reteller if I wrote memoir or essay, but I rarely do. I don’t have to be faithful to any particular truth in fiction when it comes to the incident that may have inspired it.

SR: With every story feeling like a million eyes alongside the reader’s on its characters and the specific interiority paired to images within “Presumido,” it’s clear that the gaze and its importance is still central to your works. How would you say the importance of the pictures you paint for us and your characters to consider has morphed over your writing career?

MM: I keep trying to come up with an answer to the “cinematic” whenever I’m asked this question. I’m asked about this a lot, and I feel like I should have an easy answer, but it changes so much with each story. With “Presumido,” Juan is a character who is both looked at and engages in looking, but he’s ultimately a powerless kind of character. He doesn’t know what to do with all the looking. In the story, he’s always been aware of glances, studied stares, and knowing looks. It’s a queer sensibility at work, the awareness one must have about the momentary gaze that can signal everything to someone who knows exactly how to read it. In my writing, I think it’s only intensified. I give as many details as I can in the briefest of exchanges, knowing that a whole story can spin out of assumption and presumption.

SR: All your stories are interconnected, characters unknowingly sailing past one another more frequently and creating a realistic web where one character’s epiphany is just a blip of color to forget from another’s point of view. Have there been any times where you’ve sought to expand on a perspective from a previous story and decided it was not working? What is the line, the defining aspect between one of those and “What Kind of Fool Am I?” and “Compromisos,” two stories in which we can glimpse back at earlier characters and round out new aspects of their lives?

MM: It comes back to whether or not a character can offer something specific and exact to their mention. In those two stories, we know enough about all of the characters that we, as readers, get to add our understandings—we know all sides. That’s why I do it when I see a chance to do so. Sometimes, in drafting a story, I sketched out what that story would look like from a particular point of view but, having decided that it wouldn’t work, I still had some new knowledge about that character. It’s more intriguing to me when they are absolutely peripheral, like Severina is in “Presumido” and even more so when she pops up in “That Pink House…” That speaks to me deeply about how small towns actually are—people are in passing all the time.

SR: In the inverse of the “there’s always more to say,” there is “there’s not enough time to say it all, so what do I have to sacrifice.” Personally, I would have loved to read more about Goyo and his refusal to be an obligation for another to attend to. Looking back, can you talk about regret for not returning to a plot or set of characters and surprise about which ones readers latch onto?

MM: This is related to the last question, I think, and there’s nothing stopping me from bringing Goyo back. I didn’t have enough about him to command another story, but I had many notes in my drafting. My mentor once said about a story in The Faith Healer of Olive Avenue, “You know, Manuel, this is really a novel,” and I appreciate when a story can feel quite full. Its ending suggests a resolution only to the conflict we’ve been presented with, but that’s there’s still curiosity about the life represented. But what do you tell about that life? A wonderful example of that is Caesar in Edward P. Jones’s Lost in the City. He appears in a story called “Young Lions” in that book and returns—many, many years later in his life—in the story “Old Boys, Old Girls,” from All Aunt Hagar’s Children. Could that have been achieved in a novel? Absolutely. But that these important arcs are crystallized via a short story is bracing and inspiring. They’re masterpieces.

SR: You’ve mentioned that your position at University of Arizona is what kept you writing: your need to be contributing to a greater conversation. There’s an overwhelm of expectation when you’re questioning where your writing fits into the bigger picture as you're writing it. I'm curious to how you’d compare writing now to how it was to write “Campo,” freshly out of your MFA and able to indulge in the absence of workshops and prying eyes.

MM: The difference is being a professor and being a student. Or rather, not being a student any longer. Being part of the academy as a professor requires consistent production, sometimes on a timetable that is not one’s own. I’ve been lucky in that regard. The pace of my production has been enough to satisfy the requirements without jeopardizing my artistry. I’m a slow writer and I have no wish to publish something just for the sake of doing so. I write more freely when I know that the only person I have to answer to is myself: not a deadline, not a contract, not an anthology request, not even a prompt. When’s there’s nothing except me and the page, as it was when I wrote those first lines of “Campo,” I feel quite liberated. I still remember that day at Collegetown Bagels in Ithaca when I put the first words on the notebook. No one was going to see it, I told myself, unless I wanted them to.

SR: How has moving back to the Southwest from the East Coast influenced your writing? Though most of your works take place in California in a very exact time period, does a return to the borderlands now reauthenticate, reacquaint you with the landscape and audience you write for?

MM: I’m closer to California, so I get to see it more. I’ve spoken a lot about how hard it has been to write in the last decade and have guessed about a lot of reasons. I do wonder if my proximity to the Valley had a slightly negative effect. I get to see my family much more often now, sometimes twice a year. The longing doesn’t build up like it used to and my senses aren’t as hungry. Also, Tucson reminds me a lot of Fresno. Except for the Catalina Mountains and the rich snowbirds, it’s basically the same place. I know that I’m more easily moved to write the Valley when I miss it most, so that might be one factor.

SR: Helena Maria Viramontes always comes up alongside your name, as well as praise for her mentorship, and you honor the late Donald B. Burroughs in your acknowledgements as a mentor. At the same time, there are many that reserve the same spot for you in their works. Could you discuss this circular aspect of mentorship in the writing world? What has it been like to be mentored and how does that influence how you try to mentor others?

MM: This question really moves me because I’ve been teaching at the university level for fourteen years now. I hope that some of my students have seen me as a good mentor to them. Sometimes people think that a mentor shapes our work, that we must sound like them or think of story in the same way. But it’s really about confidence--an assist in learning how to recognize and respect our own processes. Helena encouraged me to speak up in my work. She always says that I give her too much credit, but she kept urging and urging, and I was an extraordinarily shy and reticent student. She broke through because I learned to trust that she wanted the best for my talent—she believed in it before I did and sometimes I think we need to hear that to feel truly empowered.

Donald is a different sort of mentor, but the same principle was at work. He was a teacher at my first job out of college, when I had come in as a one-year replacement for another high-school teacher on leave, Joan Soble (who I also mention in the acknowledgments). He was an older Black gay man from the South, full of confidence and wit and literary knowledge, with a real gift for storytelling. But he was also a great listener. Both he and Joan shared an ability to listen to me where I was—neither of them was ever prescriptive or judgmental or impatient with me. They let me figure things out, gentle in offering pathways I hadn’t thought about. I like to think I do that for my students now. Just listen to them, affirm them in their ability to embrace their power to make good decisions, the right decisions. Thank you for asking about Donald. I feel so lucky to have crossed paths with him in this life. I miss him dearly.

SR: In that same interview, you said “When I returned to writing short stories, it was not necessarily a source of comfort, but it was something I knew I did very well.” This rings so true in a time in which what we enjoy is being corrupted into mere employment. Was this a feeling you dreaded confronting while pursuing your MFA at Cornell University? Would you care to share the closest you came to quitting and what drew you back from that point?

MM: While I did my MFA, I worked on a novel. Stories came later and I want to say they came naturally—the program did its work without me even knowing it. I may have been shy and reticent, as I said earlier, but I was absorbing a lot because everyone was working on short stories. I ended up having my own ideas about what I thought a story could and should do and I set about putting that to practice.

The closest I came to quitting was about 2014 or 2015. I wanted to go back to New York City, where I had been before I took the job at Arizona and where the vibrancy of city life had always inspired me to keep writing. I wanted to separate my writing from my employment very badly, but after years of explaining to my family what a tenure-track job was, there wasn’t any way to explain to them why I’d leave it. So I stayed patient with myself and kept going.

I think the turning point came when I had finished about three stories—I simply stopped thinking about a book or a finished project and encouraged myself to concentrate on each story as it came. I had to relearn embracing the act of creating in the way I had it in New York—back then, I wasn’t doing it for any gain except for how it satisfied me in the few hours I had in quiet, meditative silence. Creativity is personal and precious. I had to remind myself that no one determined its value except me. Not the academy, not a publisher, not a journal. Me. That’s really hard to do, especially when the world only thinks you’re working when you’re publishing. That simply isn’t true.

SR: Zigzagger and The Consequences seem to share the trait of starting out once you started moving on, with you already having started Faith Healer by the time the imprint expressed an interest in the former and the “crisis of confidence” that lagged this collection for nine years. Yet you continued writing, and you finished The Consequences with pride. What advice would you offer to others who are facing similar crises of faith in their own work?

MM: When I turned in the novel to my former publisher, my editor’s short response was “This is too cerebral,” which lingered in my head for years. It really undercut me for a long time and made itself an unconscious starting point whenever I was drafting new work. Am I overthinking this story? I’d ask myself, until I realized I was letting someone’s else sense of my art guide what I was doing. It’s one reason I left my publisher and knew I had to start over somewhere else if I was going to be able to keep writing.

The short of it: Answer to yourself and only yourself. As someone once told me, “No one is waiting for it,” which sounded so harsh to me at the time. But what a liberating truth! No one knows you’re drafting, sketching, listing, revising. And no one knows if you’re giving up, stalling out, procrastinating. You do, though. Persistence is so rewarding. The harder the challenge, the louder the negative, the better it feels when you conquer it.