Dylan Brie Ducey

Dylan Brie Ducey's fiction has appeared in Sou'wester, Gargoyle, Four Way Review, The Pinch, and elsewhere. She received the Carlisle Family Scholarship to the Squaw Valley Writers Workshop, and her MFA from San Francisco State University. She lives in California with animator Tom Gibbons and their two children.

It’s 1997, September, and I’m living on a movie set. It is not a glamorous-big-budget movie set. There are no caterers here, no dressing-room trailers or makeup artists, no set dressers or hairdressers or best boys. This is a low-budget independent film set, inside a cinderblock warehouse in east Oakland.

I am sitting on my exercise bicycle on the first floor of our live-work space, wearing shorts and a tank top. It is hot, even down here, because the warehouse has no insulation and no windows. It’s pitch dark. I’m listening to Prince on my Walkman, probably Dirty Mind because it’s fast and, well, dirty. I want to check my mileage, so I turn on my flashlight.

“Hello!” says Tom, from the other side of the room. He is my boyfriend. What he means is ‘turn off the goddamn flashlight.’ He is the director of the film and he’s right in the middle of a shot.

“Mileage!” I retort, somewhat defensively. I insist on doing ten miles per day on my exercise bike, but I feel a little guilty about it because it interferes with the film. I glance at the odometer. I’ve only done three miles. I turn off the flashlight and keep pedaling. Technically, I knew what I was getting into when I moved to this cinderblock warehouse in east Oakland, but there are days I have to ask myself what I was thinking.

Tom Gibbons is a stop-motion animator. The film he’s making is an animated short based on “A Hunger Artist,” the short story by Franz Kafka about a performance artist whose art form has become obsolete. Stop-motion is done with puppets, rather than cels or drawings. It is slow, painstaking work. As Tom said to me once, “I’m animating the guys, frame by frame. Move the puppet, take a picture. There’s not much to it. If you’re really fast, you can do about four seconds [of footage] in a day. It’s glacial.”

Tom has a BFA in Illustration, and taught himself stop-motion. He was part of a small group of American stop-motion animators, including Tim Hittle and Webster Colcord, who were among the last to master this exacting art. Tom made a number of short films very early in his career. Professionally, he started out working on stop-motion commercials in the mid-1990s, then on a Saturday morning cartoon called “Bump in the Night,” and finally on the full-length feature “James and the Giant Peach,” directed by Henry Selick. Tom is now working at Tippett Studio in Berkeley, for Phil Tippett. Phil is the legendary stop-motion animator who animated the creatures in the first Star Wars movie for George Lucas. Now Phil has his own shop, and he personally recruited Tom to come work there. Phil is not a person who calls people, but he called Tom on the phone, asked him to come in for a stop-motion test shot, and hired him on the spot. Tom is the only person Phil has ever hired on the spot, and from the very beginning the two of them had a kind of soul connection. For decades at the Studio, Tom will be considered not just Phil’s right hand and his friend (creating no small amount of envy and resentment), but nothing less than the next generation of stop motion genius. During this period in the late 1990s, Tippett Studio is buying computers and the stop-motion animators are learning how to animate in CG. Phil especially wants stop motion animators, who understand the art of moving a puppet, how to convey emotion in a physical way. This is something about which future computer animators will be clueless. The last American stop-motion feature films have already been made (“Nightmare Before Christmas,” “James and the Giant Peach”), and the era of computers is beginning. It is this type of sea change that is a major theme of Tom’s independent film: The Hunger Artist clings stubbornly to his art form, but his audience no longer cares. The audience is a fickle audience, and has moved on to the next thing.

I do not think of myself as involved in Tom’s film. Still, I live here. I moved to the warehouse because I was sick of driving from my studio apartment in Berkeley to Tom’s place and back, and, not incidentally, because I’m in love with Tom and know this is a permanent relationship. It took me a while to figure that out, though, and while I was figuring that out, Tom’s friend from art school, Dave, bought a 3,000 square foot cinderblock warehouse in what’s known as New Chinatown. The idea was that Dave would paint and work (he’s a machinist) and live in the front of the warehouse, and he would build a separate live/work space for Tom in the back. The ceilings being twenty-five feet high, Tom knew he could set up lights and shoot a film there. It would be their own utopian artist community. But, since the warehouse was a strictly industrial space, this meant building lofts for sleeping and putting up a giant wall to separate Tom’s apartment from the rest of the warehouse, and adding staircases and skylights, as well as modern conveniences like showers, stoves, and a washing machine. Tom, Dave, and Dave’s brother Tommy, start working on the space, which takes about six months to build.

Tom and Dave are visual artists, men with trucks and propane heaters, and there isn’t much physical comfort in their world. However they have girlfriends, too, women with bookcases, clothing, shoes, and jewelry, and other feminine accoutrements. Dave’s girlfriend is more patient than I am – she moves in right away, before her space is even built. She and Dave cook their dinners on a Coleman camping stove and it’s romantic. I remain in my nice studio apartment in Berkeley, with its radiators and walk-in closet. Later, when Dave and Tommy have put the finishing touches on Tom’s space, I give up my apartment and move in.

Tom and I sleep in a tiny bedroom (6.5’ by 15’), large enough for a double bed at one end and my desk at the other. There’s a large skylight directly above my desk. A catwalk connects the bedroom to the kitchen and living room. Here there is a couch, a small kitchen table, a sink, refrigerator, a tiny gas stove, and a kitchen counter. The whole room is 15’ by 20’, and there’s also a bathroom with a shower stall. It’s a very small space for two people, so small that I keep most of my books in boxes out in the warehouse.

What makes the space seem even smaller is the fact that there are no windows to the outside. There is a window in our bedroom so that I can see our living room when I’m sitting at my desk. But if I want to see the sky, I have to crane my neck and look up through the skylights, which are very dirty. Or, I can go downstairs and walk all the way through Dave’s huge workspace, past his live space, through the giant roll-up door, and then outside. Sometimes I feel so claustrophobic in our space that I grab my keys, and get in my car and drive, just because my car has windows.

The space is already windowless and close, but there is a new development: The entire upstairs is now obscured by black duvetyne curtains. Tom has hung these curtains from the ceiling all the way down the length of the catwalk, and then at a right angle next to the living room. This is to block all the light coming from the skylights; it makes the downstairs absolutely pitch dark for the purposes of shooting, and it makes the upstairs pretty dim. There is also a blanket covering the living room skylight, an attempt to lessen the broiling summer heat. The upstairs of our space is like a greenhouse in summer. It’s always hotter inside than it is outside. Tom has also installed a blind above my desk in the bedroom, which can be drawn directly under my skylight. This is to reduce both the heat and the light; in summer the latter is so intense that I cannot see the screen on my laptop at all. The overall effect of all these curtains and blinds: I live in a cave.

So, I’m living in a cave/film set, but I dismiss all questions regarding my own involvement in The Hunger Artist. Some friends of Tom’s come over, a boy named Bobby Beck and his girlfriend. Ten years later, Bobby will strike it rich as the founder of Animation Mentor, an online animation school, but now he’s just another young animator looking to glean wisdom from Tom. Meanwhile, the girlfriend asks if I’m “helping” Tom with his film. She is completely serious. I laugh. Please, I say. I’m a fiction writer. But I’m not being entirely truthful here, since I actually have helped: I wrote a grant for the film at the kitchen table upstairs, a grant for $4,500 that Tom received from Film Arts Foundation in San Francisco. (Before the film is finished I will write a second grant, and FAF will give Tom another $7,500.) The writing was the easy part. What was insanely difficult was talking Tom into applying, and then getting him to discuss his vision for the project, a vision I knew was very clear in his mind. He had been thinking about the story ever since he borrowed a book of Kafka’s short stories from me two years earlier, before we lived together. That was when he started drawing concept art for the film.

The Hunger Artist is a big project, and it will take much longer to finish than either of us anticipates. When post-production is finally done, the film will turn out to be sixteen minutes in length (very long for an animated short.) It will be described by one reviewer as “achingly beautiful.” By the time the film has gone on the festival circuit, and been short-listed for the Oscar and placed in the Harvard Film Archive, Tom and I will have gotten engaged, moved twice, gotten married, bought a house, and had a baby. Among other things.

But all that is in the future. Right now I’m pedaling on my exercise bike in the dark, just like I do every day, and Tom is filming the slow, agonizing frames of a shot. I’ll call this shot “The Impresario Raises the Hunger Artist’s Arm to the Audience.”

Twenty feet away from my exercise bike are fifteen lights mounted on c-stands. These lights take up a lot of room, and involve a lot of electrical cords on the floor—I have to seriously watch my step when making my way to my exercise bike. The effect of the lights is muted by the gels—sheets of colored plastic—which cover them. The lights are pointed at the Arena Set; it is eight feet wide by fifteen feet long, and built (by Tom) of wood. The back of the set rises fourteen feet high and is painted blue and grey to represent a cityscape, with little windows out of which imaginary people are watching the show. The show is, simply, the Hunger Artist. In the film, the Hunger Artist is doing a forty-day hunger performance in the center of the arena, watched by an indifferent audience. His handler, the Impresario, presents him every day as a spectacle to be watched.

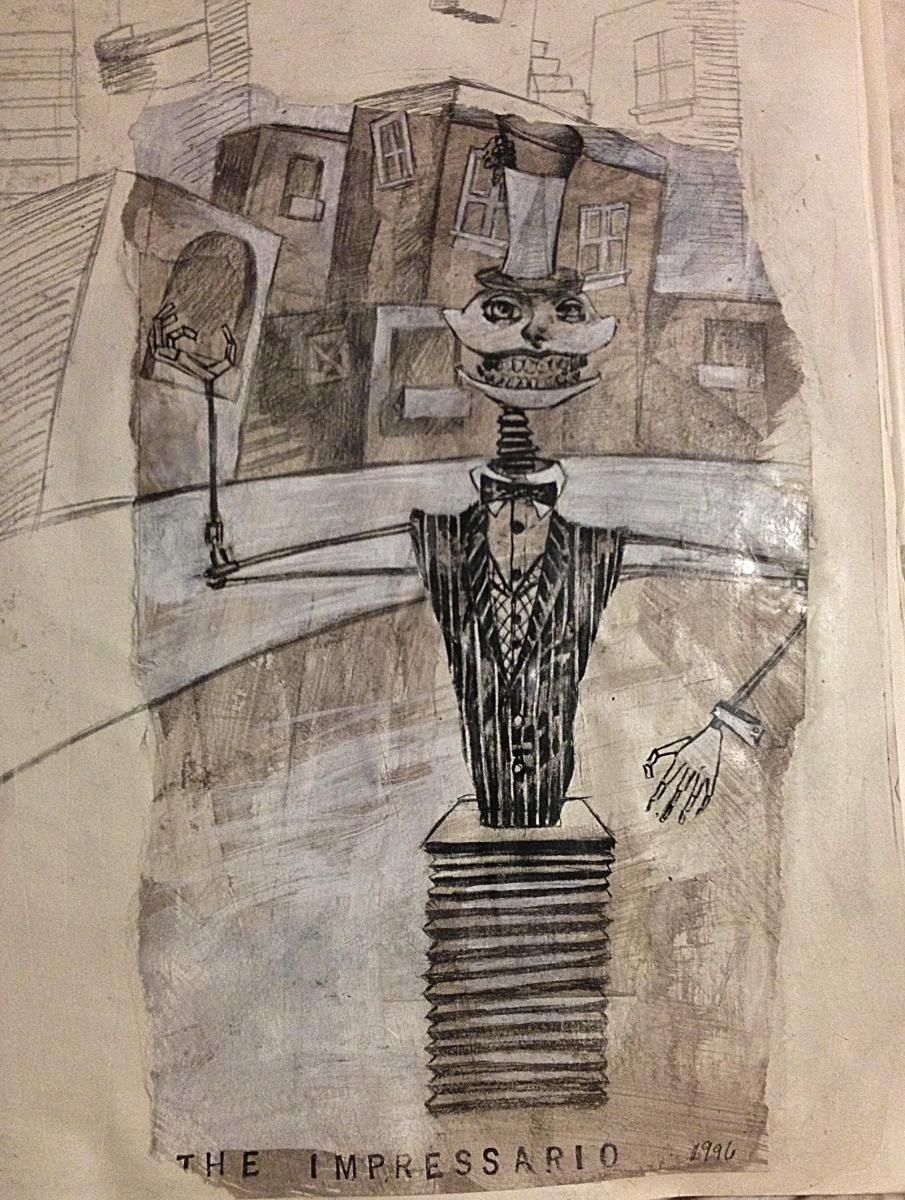

The Impresario is a clown-like barker who, at fourteen inches tall, towers over The Hunger Artist. The Hunger Artist is a slight little man, nine inches tall.

The Impresario is made of a brass armature (handmade by Tom), an old optical printer bellows, epoxy, and a fur coat, with glass doll eyes. His eyes were taken from two different dolls – different sizes and different colors – giving him an even more sinister effect. The Impresario’s hands are foam castings of a baby doll’s hands. He’s got a large top hat and a giant clown-like mouth that goes up and down like a piston – that’s the purpose of his hat: When he takes it off, his mouth opens; when he puts it back on, his mouth closes.

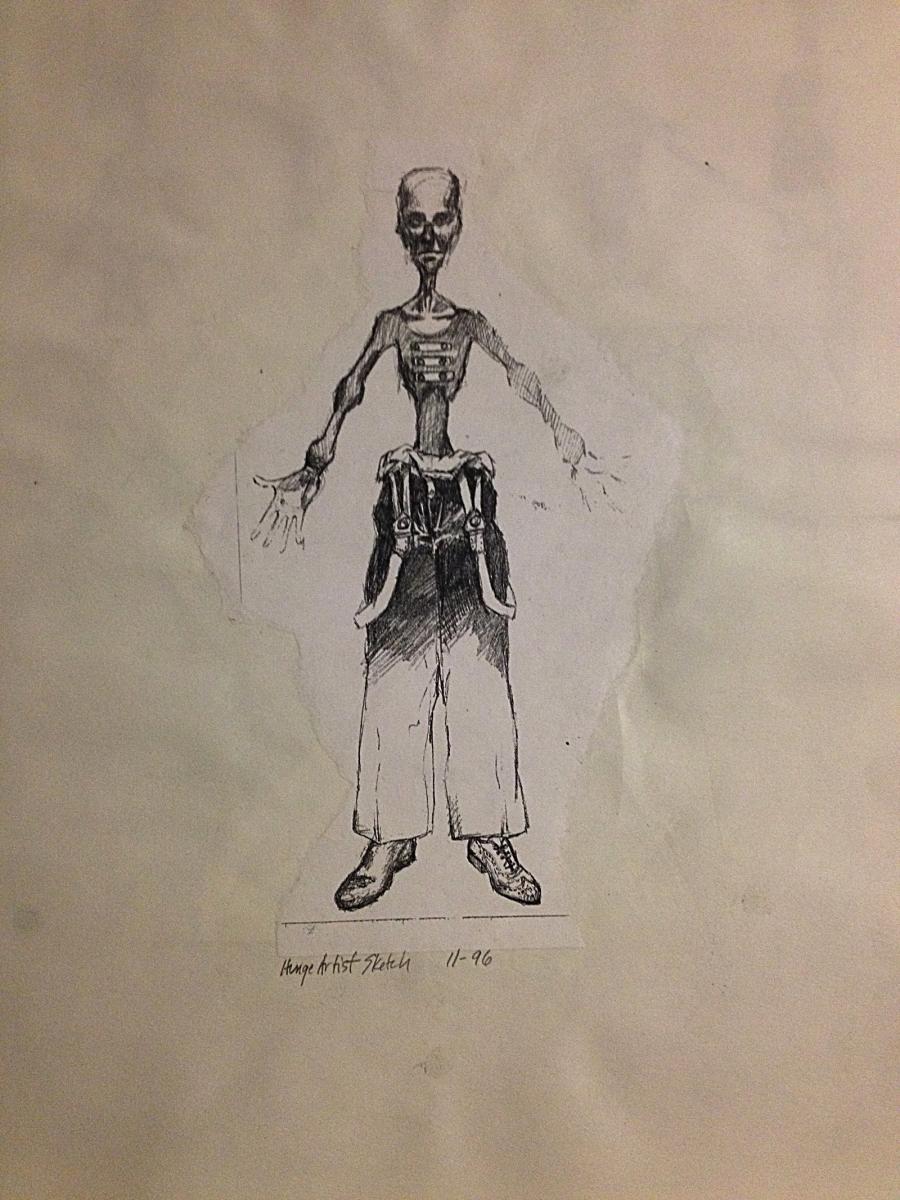

The Hunger Artist is a foam puppet with a steel armature, designed by Tom and made by master machinist Peter J. Marinello, in Los Angeles. The Hunger Artist has a plastic head, made by Tom, and glass eyes. He wears leather shoes, black pants, a white button-up shirt that comes to his waist, and suspenders that animate (they have wire in them). Victoria Drake made his clothing; she lives in San Francisco, and Tom met her at Danger Productions in the early 1990s, when they were working on Bump In the Night. Victoria also made the Impresario’s fur coat.

There are also five Minions on the stage. These are small, flat 2-D characters made of styrene and paper, painted black and white, and wearing black top hats. The Minions assist the Impresario in the handling of the Hunger Artist. When the Hunger Artist first rides onto the stage on his cart, the minions are pushing it.

Tom’s Bolex camera is set up on a rig he made that tilts and pans the camera left and right, up and down. The Impresario puppet stands beside the Hunger Artist as he stands on his cart in the middle of the Arena. The Hunger Artist stands idly by as the Impresario eyes him malevolently and then lifts his emaciated arm to the audience, or, in this case, to the camera for the movie audience to see. Frame by frame, Tom moves the puppets and clicks off one frame after another on the camera. It is tricky, because he has to make it look as though the Impresario is actually moving the Hunger Artist. Tom also must be careful to make sure that all the lights on the set stay on and don't burn out, and that any light leaking from the warehouse doors or windows is sufficiently blocked; such light can cause a flicker to occur in the footage.

It takes about a minute to move the puppets in unison for each frame of film. It takes twenty-four of the moves to make one second on film, so Tom cannot afford to make any mistakes. The frame grabber can give him a rough idea of what he has shot, right away, but he’ll only see any mistakes after the film comes back from Monaco Labs in San Francisco. This means that if something bad happens, then the days it took to shoot the shot are lost and he’ll have to do it all over again. Tom rides his motorcycle to Monaco, south of Market Street, several times a week, to drop off and pick up film. Much depends on Monaco, and when someone there goes on vacation or loses a Hunger Artist shot (yes, that has already happened several times), it is a big deal.

As the Impresario raises the Hunger Artist’s arm to the camera, Tom also wants to refocus the camera, to simulate what happens in a live action film where the cameraman is following the action, but again, in stop motion he must animate the camera’s focus frame by frame. So as the Hunger Artist's hand is raised, Tom slowly starts to "rack" the focus to keep the hand sharp, while the background goes slightly out of focus.

Problems crop up continually during shooting. If lights burn out, Tom has to stop the shot, replace the light bulb, and rebalance the light. Another issue is that the stage of the Arena Set is made of sand, so he has to be careful not to touch the sand while he animates. Another thing: In order to do camera moves, he has to clamp six-foot arms to the side of the camera so that when he moves it, it will register six feet away at about half a millimeter. With every shot, the camera is basically moving, along with the puppets.

Then there is what is arguably the biggest problem: Tom has two very large power stats—giant coils of copper wire that he uses to balance the power running into the lights. One of the power stats catches on fire, twice, because Tom can’t get the wiring right. Another time, Dave knocks on the door of our space while Tom is still at work. He says there is a burning smell in the warehouse. It turns out that a plastic casing in the big fuse box is melting, and Dave thinks that Tom’s new frame-grabber is causing this. Of course the frame grabber isn’t the cause—and even I know this. A frame grabber (also known as a video assist) is a low-resolution computer program that uses a video camera to store a video representation of what the camera sees. Tom uses it to see an approximation of what he’s just shot, but only an approximation. To see the shot in detail he has to wait until Monaco has developed the film.

Anyway, as far as the burning smell goes, the frame grabber hardly uses any power and is the least of our problems. The real problem is that the lights for the Hunger Artist use a staggering amount of power every day. (I’ll add that Dave, the machinist, also uses an enormous amount of power to run his mills and lathes—the monthly PG&E bill for the warehouse is very large.) That night Dave shuts off all the power to the warehouse. Fortunately, Tom and I have a gas stove, and a supply of candles. I make pasta by candlelight. Tom comes home from work, and we eat dinner together. When he is finished eating he goes downstairs to shoot and leaves the dishes on the table. I have already washed Sunday night’s dishes for him, before he got home, so that I could cook dinner. I tire of this, and of the unstoppable machine that is the Hunger Artist.

It’s winter now, and I am a writer, not an animator. I like windows and warmth, and order, and acres of books, none of which I can find here in the warehouse. I am a writer but I’m perpetually blocked. Living with the Hunger Artist is an all-consuming experience that leaves no room whatsoever for me—the person I am. I can’t write when I’m too cold or too hot. I can’t write when the lights go out suddenly, and I can’t write when there are no windows to look out of.

It is ridiculous that I am in love with a stop motion animator. We struggle continually over who gets space for their art—and right now I am losing that struggle. Later, much later, we will solve that problem by buying a house (Heat! Windows!). We will spend $10,000 to cut a hole in the kitchen ceiling for access to the attic, installing a ladder, a floor, windows, and electricity. The attic will become my office, my permanent writing space. Then, we will spend $30,000 to build a separate studio on the property for Tom—but that’s way in the future, too far to even imagine, and in fact I cannot imagine it right now.

In the meantime, I’m getting fed up with the space. As in, totally fed up. It happens when I spend a lot of time here. It’s always cold inside, and the air is damp. It gets so cold inside the space that sometimes we turn on the oven and open the oven door for warmth. In the mornings, which are positively frigid, I use a propane blast heater that Tom mounted on wheels: It’s a five gallon propane tank with an open face porcelain burner that sits on top at a right angle, so it looks like a little pot-bellied robot with a rectangular face. You turn on the gas and light the burner with a butane torch, and the whole face of the robot turns into an open flame. Then you wheel it around the space wherever you go, to keep warm. I am very good at lighting this heater at 6:30 in the morning before I step into the shower.

Anyway, the space is cold, and a perpetual mess. One small room serves as the kitchen, dining room, living room, and dressing room. I can clean it up five times a week, and it’s always a pointless exercise. One day I’m running the electric heater in the office/bedroom, and making toast in the toaster oven in the kitchen. This blows a fuse. I try to find the fuse box (conveniently located behind my shoe shelves), but it’s very dark. I start throwing my shoes all over the room in my fury. I cannot see the fuse box, therefore I cannot get the lights back on, and I am so mad I could spit. Tom went to Monaco Labs a couple hours ago and I have no idea when he’ll be back. I become furious, and I want to break things, and I have to leave. I grab my keys and wallet and I flee. Thank god for my car. It has windows.

The Hunger Artist

The Impresario