Jacqueline Doyle

Jacqueline Doyle’s award-winning flash fiction chapbook The Missing Girl is available from Black Lawrence Press. In addition to a previous essay in Superstition Review, she has published creative nonfiction in The Gettysburg Review, Passages North, New Ohio Review, Catapult, and Fourth Genre. Her work has been featured in Creative Nonfiction’s “Sunday Short Reads” and has earned seven Notable Essay citations in Best American Essays. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.

The Dream Lives of Objects

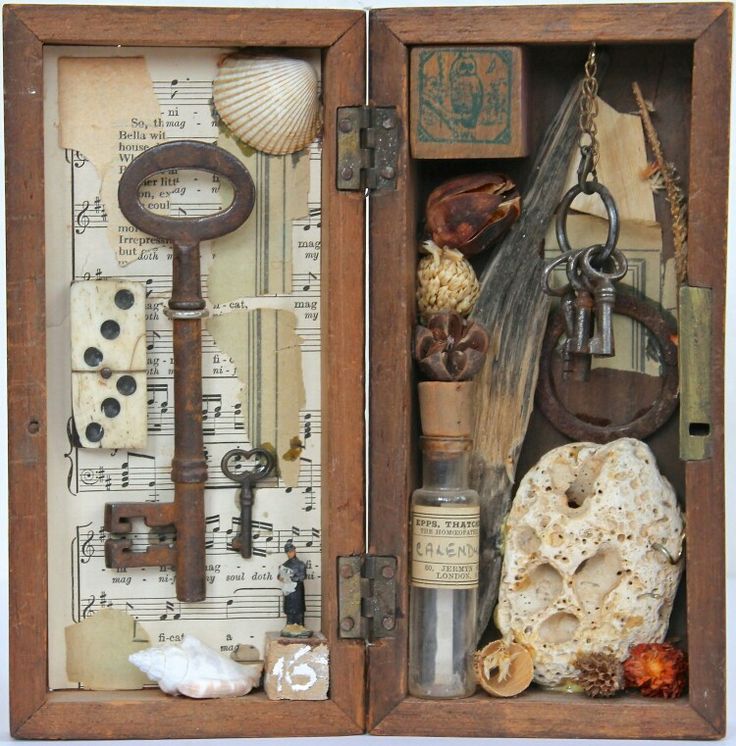

Keys

What makes Joseph Cornell’s shadow boxes so haunting and evocative? In the shadow box filled with keys, why are there so many? Keys hint at a solution, a meaning to be unpuzzled, a mystery to be deciphered. Are the other objects in the box clues? What needs to be unlocked?

Dice

Two antique dice, a pair of threes, one of them chipped, recall childhood board games missing dice and pieces, a stack of tattered cardboard boxes on a shelf: Candy Land, Chutes and Ladders, Monopoly, Parcheesi, Scrabble, Clue, the card game called Old Maid. For years your father played chess with you and your brother every morning at 6:00 am before he left for work. The chessmen were ivory, a set he’d brought back from a voyage to India and Egypt before he was married. Your favorite piece was the Queen, a woman free to move in all directions.

Keys

The ring of keys in the shadow box resembles keys you don’t recognize in your junk drawer. Old apartments and mailboxes? Storerooms and cabinets from past workplaces? When you left your first teaching job, the administration wanted the key returned for an office in a building that had been knocked down. Getting the necessary forms signed for the lost key required an entire afternoon. Even useless keys are apparently worth something to someone. There were many bureaucratic edicts from the university administration that defied explanation. You considered assembling a collection of outlandish memoranda.

Sheet Music

The crumbling musical score visible only in fragments suggests life as a musical composition rather than a game of chance, inspiring memories of the upright piano in the house you grew up in, and heaps of sheet music in the wooden piano bench with the hinged top. You remember playing the Moonlight Sonata at the white-haired piano teacher’s house on the hill, her silver white Husky slumbering before the fire. Your father’s disappointment when you chose an easy piece to play the night he wanted to show you off for company. Did you deliberately thwart him, or were you just nervous about making mistakes? Maybe you felt that art was private, not for public display.

Keys

Cornell’s keys unlock memories of fairy tales where maidens were locked up, or forbidden to open locked boxes or locked rooms. Rapunzel locked in a tower. The miller’s daughter locked in a room to spin straw into gold after her father boasts of her skills. Bluebeard’s wives unable to scrub the blood off the magic golden key after they unlock the forbidden chamber. You loved fairy tales, the grislier the better. Even as a child, you were suspicious of morals imposed on the stories. Surely Bluebeard’s wives weren’t being punished for curiosity, any more than Eve precipitated the Fall by eating a forbidden apple, or Pandora loosed evils on the world by opening a forbidden box. Fairy tales didn’t need to mean something.

Seashells

On visits to the Jersey shore in the summer, you scavenged for shells for hours. Dragged up from the ocean floor, polished by the sand and waves, deposited on the glistening beach amid sea foam and tangles of kelp, every shell was the remnant of a dead mollusk, a past dwelling spiraling inward to protect the inhabitant. You were amazed to hear the ocean when you held a conch shell up to your ear. How was vastness contained in the miniature? You kept buckets of shells in the bookcase that held your toys, shells on the shelf by your bed, sometimes a shell in your pocket, along with a lucky rabbit’s foot purchased at the local stationery store. You were superstitious. You believed in talismans.

Key

A large key dominates the shadow box, rusty, a reminder of some bygone residence, its occupants long since dead. Did they leave their fingerprints on the key and on crystal doorknobs and wooden newel posts? Do they haunt their former house, or has it been razed, the Victorian doors and windows and mantels sold for salvage? The unpainted, three-story stucco house in northern New Jersey that you grew up in, built in 1914, had several owners before your family, and has gone through several owners since. You drove by a few years ago, a detour on a trip from Maine to Manhattan, and barely recognized the house and yard—painted, landscaped, the gnarled lilacs gone, the sleeping porches glassed in to become rooms. Rich people live there now. You liked it better before the dramatic renovation—ramshackle and rundown, still sheltering past secrets, with unused attic rooms and unexplored alcoves in the dank basement. You often dream of the house.

Honeycomb

The fragment of a honeycomb, once golden and dripping with honey, is now dry and gray, feather-light. Like the separate compartments in Cornell’s boxes, and the labyrinth of rooms in old houses, the honeycomb’s tiny hexagonal cells proliferate, an intricate architecture. Something lived there once. You can see your father, allergic to bees, climbing a tall ladder dressed in gloves and a pith helmet with a veil, preparing to destroy a beehive under the eaves of your three-story house. Bats lived under the eaves as well. On summer nights they flew high above the back yard, emitting high-pitched squeaks you could barely hear. The heavens were awash with stars. Fireflies winked all around you, infinitesimal points of light, here, there, here. The yard smelled of fragrant honeysuckle and damp earth, the grass still wet from the rotating sprinkler.

Pharmaceutical Bottle

An antique bottle containing a clear liquid, Calend handwritten by the pharmacist on the printed label, asks you to fill in the missing letters. Is it Calendula, a botanical remedy for fever and cramps? You liked to explore your mother’s medicine cabinet in the small, old-fashioned bathroom off your parents’ bedroom. Q-tips and cotton balls, red lipsticks in gold cases, loose orange powder from compacts, bobby pins, prescription medications for her headaches and allergies in orange plastic vials, an array of perfume bottles: Chanel No. 5, a vertical rectangle; Shalimar, round with a glass stopper; Tabu, dark and squat. A peach-colored container of perfumed talcum powder with a fluffy powder puff on the back of the toilet. The mingled smells, acrid and unpleasant, of perfume and urine and mildew and cigarette smoke and hot dust on the radiator. The thrill of trying on your mother’s lipstick and rouge when it wasn’t allowed.

Keys

Cornell’s keys make you think of the small key for your father’s desk drawer. The tiny keys for the red diary you kept as a child, and for the jewelry box with a mirror inside the lid. You used to rummage through your mother’s jewelry, trying on pearls she never wore, and the copper bracelets and necklaces your father had given her when they were courting, sifting through inherited trinkets from grandmothers and great aunts you’d never met— a string of amber-colored crystal beads with a broken clasp, a diamond engagement ring, an ivory necklace with carved elephant beads, a gold locket with miniature sepia photographs of someone’s husband or fiancé—long since gone and forgotten. So much was lost, or given away when you cleared out your mother’s apartment after she died. You kept one copper necklace, a few rings, but other women must be wearing her jewelry now.

Toy Blocks

Two antique wooden blocks are tucked into the shadow box, children’s toys, one imprinted with an owl that presides over the scene like a tutelary deity. An owl hoots softly in the middle of night where you live now in Northern California. You were over fifty before you saw an owl in the wild. Did you see it? Or did you just dream you saw an owl? Cornell’s assemblages often feature owls and parrots and other birds. You remember wooden blocks like these from your childhood, imprinted with the letters of the alphabet. They were already old, maybe your father’s once, or even his father’s. You read from your father’s childhood copy of Alice in Wonderland, and memorized all of “Jabberwocky.” “’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves, did gyre and gimble in the wabe.” The deep satisfaction of words that made no sense. Of useless and discarded objects. Shadow boxes as sacred reliquaries for lost and found bric-a-brac, scraps of old engravings and maps of the constellations, broken and abandoned playthings predating your birth.

Stones

Among the natural objects in Cornell’s box is a large white stone riddled with holes from erosion—something a child might put in her pocket and carry home to display on the windowsill, or hoard in a box under her bed. A treasure forgotten when she grew older. You kept a small rock collection in a clear plastic box, and were stirred by the magic of feathers, collecting them and pasting them into slender stocking boxes with labels for each: robin, chickadee, titmouse, sparrow, flicker, woodpecker, Canadian goose, swan. Your favorites: blue feathers with black stripes and white tips from blue jays, red feathers from male cardinals, and iridescent, midnight blue feathers from the wings of male mallard ducks. A pheasant tail feather with ochre and black stripes. Your feather collection served no purpose, beyond giving order to the marvelous.

Keys

You lock up at night to keep out intruders, to protect your loved ones and possessions. To create a space safe for dreams, where the objects housed in your unconscious emerge, resonant and mysterious. Cornell’s shadow boxes unlock the portal to memory, reminding you of something forgotten, a time in childhood when natural and man-made artifacts were saturated with significance, transcending rational interpretation. The ordinary became extraordinary simply because it was prized. Wonder was more than enough.