Emily Townsend

Emily Townsend is a senior English major at Stephen F. Austin State University. Her nonfiction and fiction have appeared in The Bookends Review and Junto Magazine, and are also forthcoming in The Thoughtful Dog Magazine and Sink Hollow. Her nonfiction essay has been nominated to represent SFASU in the AWP Intro contest. She is not terribly scared of honeybees, but she feels mega uncomfy when they want to collect the sugars in her salad.

Consider the Honeybee

*

Consider the honeybee, that tiny yellow and black thing that pokes into your Dr. Pepper on a picnic, for a moment. The first Apis bees appeared 34 million years ago in the Eocene–Oligocene European boundary. The Apis nearctica is the only known species from The New World, found in Nevada fourteen million years ago, during the middle Miocene period. Most species have been ushered into honey farms for their beeswax and nectar, unwillingly relocated to the wrong habitat, where they are born into a mini society that bees have never known, and will not live long enough to warn its descendants.

*

Flowers, most obviously, allure honeybees for pollination, as well as the colors of blues and yellows. A honeybee despises marigolds for its unpleasant scent and irritating red shades. They have an average lifespan of 122-152 days: four months, seventeen weeks, 175,680 minutes. Those born in the beginning of winter rarely learn to fly. When the temperature drops below 50 °F, they crowd into the central area of the hive to form a "winter cluster." The snooty queen bee resides at the center of the cluster, and the worker bees huddle around to keep her warm. In our winters, we trudge on a sweater and fuzzy North Face coats and keep moving. Bees are forced to cuddle with one another, snuggling into a burrow the size of a human’s head, shivering, quivering, trembling, and if they make it to the rebirth of spring, they only have a few days to experience their natural life outside of the hive. Like dogs who have never touched grass because they were trapped in metal shelters until adoption, bees float out into the innate world disoriented, untaught where to go. So they mosey over to foods that resemble the honey stored inside their home, foods that humans like to eat, foods that humans have stolen from the nectar to create the product that honeybees are inherently attracted to. Honeybees only think of how to feed their colony of a thousand other bees, much like how we worry about feeding ourselves to sustain a life we never asked for.

*

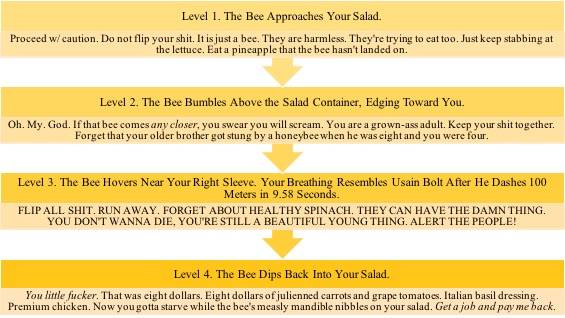

A honeybee releases an alarm pheromone at the smell of a banana because of its isoamyl acetate, an ester formed from isoamyl alcohol and acetic acid. A human emits a screech when something scary or nerve-wracking triggers their amygdala—the almond-shaped mass of gray matter inside each cerebral hemisphere, involved with the experiencing of emotions. Screams speed the delivery of the warning by stimulating the fear centers of the brain, a cautionary signal that ignites, I gotta flip my shit to show that I am afraid of this little bugger and hope it won’t sting me. Humans jerkily back away and swing their arms to surrender to a species that will not attack unless their hives are physically provoked. Humans are constantly trying to one-up each other in competitions and achievements, yet they back down at the first glimpse of a bee droning into their salad dressed with sweet vinaigrettes. Our Panera poppyseed drizzle attracts bees to the monosaccharides of fructose and glucose needed for their diet. Adult worker honeybees need four milligrams of sugars per day, and adult humans should consume around thirty milligrams daily. The difference of twenty-six milligrams should not invite honeybees to amble over to our meals: on hot days, bees will collect water from streams or ponds near their hive, yet those little sneaks like to rudely invite themselves to our table/spread/laps of our food.

So when we do inevitably flip our shit once a honeybee gets too close, they might decide to inject a stinger in our skin. If the stinger is left in the skin, the accompanying venom sac will continue to pump its poisonous substance. Other animals know how to defend themselves. Once bitten, the Australian funnel-web spider’s envenomation takes twenty-eight minutes to seep in, but death may occur in fifteen minutes. The tentacles on a Chironex fleckeri has a sting so powerful that it can kill a human in two to five minutes. A platypus, though not lethal when struck by its hind legs, has venom that can flood excruciating pain, which can develop into a long-lasting hyperalgesia. But the honeybee, the flying paper clip sized insect that collects nectar, has only one act of defense, a martyrized fight to save itself. The sting apparatus has its own musculature and ganglion—a structure containing a number of nerve cell bodies—and once the stinger is detached, the honeybee’s heart slows, the body dwindles in the swoop of air.

Honeybees don’t think of death the way we do. They don’t know how to survive losing their defense mechanism. Not a single bee lived to buzz the tale. It simply happens once. They don't know any better.

*

As soon as it is vexed, securing itself on your skin is the honeybee’s penultimate act. Driving a three millimeter stinger into your flesh is the ultimate bow—the disemboweling of its abdomen disengages its lifeline. While you are busy crying over the prick, the honeybee spends its dying moment flying around your head, lost without its lower half, signaling that it is trying to find a place to attack you again, but they are really trying to find a place to let their anatomy decompose.

Do bees have thoughts like how we are supposed to have on our way out? Do bees recollect pollinating their favorite flower? As they fall, do bees think about the burden they will leave behind in their absence? Does their proboscis thirst for a drink of sweet honey, a shot of revitalization, the hopeless desperation that maybe the food it has produced is its antidote, its cure to stinging you? As they almost hit the roots of Earth, do their antennas pick up one final whiff of the sugars lingering in your salad, much like a prisoner glancing at his last meal before execution?

There is a honeybee on the ground by your shoelaces. A small thing the size of a child’s pinkie. You realize that you were a proponent in the death of a honeybee. You didn’t kill the honeybee. The honeybee only acted in its blind defense. Go finish your damn salad, you selfish person.